Tuesday, June 25, 2013

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Buck Rogers - Looking back at Something that Looked Forward

Time Machine: Buck Rogers

Buck Rogers – all white teeth, innuendo-laden badinage, fey robots and tight jumpsuits. That’s what the name means to most of us, remembering as we do the low-brow, high-camp 1980s series from the vast stables of Glen A Larson, whence many a wonky nag and almost thoroughbred SF TV show came trotting onto our screens. The show followed Larson’s “fire and forget” approach to producing, appearing with much fanfare and running for a mere one and a half seasons before sinking into a quagmire of high mediocrity, becoming a something that today seems laughably bad. But Buck Rogers was once much more than this, entrancing several generations of Americans in magazines, comic books, radio and screen, and the sad whimper that his last hurrah endured does a great disservice to his legend.Anthony Rogers first appeared in the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories magazine. Penned by Philip Francis Nowlan, the tale was entitled “Armageddon – 2149″. It was a clever piece of science fiction that had the forces of the future waging war on one another with a variety of military inventions that have since become commonplace – infrared ray guns for night fighting, jet planes, bazookas, paralysis rays and more, though Buck’s flight-endowing jumping belt is still sadly unavailable. The famed Hugo Gernsback, at the time editor of Amazing Stories, firmly stated of the tale: “We have rarely printed a story in this magazine that for scientific interest as well as suspense could hold its own with this particular story. We prophesy that this story will become more valuable as the years go by. It certainly holds a number of interesting prophecies, many of which, no doubt, will come true.”

Many of the Buck staples are present in the original stories. Buck Rogers, an ex-WWI American fighter pilot, is a surveyor in Pennsylvania who gets trapped in a cave-in and is put into suspended animation by a strange radioactive gas. When he awakes 500 years in the future, the heroic Buck becomes a pilot once more, a secret agent and head of the Rocket Rangers. He lives in a futuristic city of “metalloglass” full of marvellous devices. His enemy is Killer Kane, an evil Mongol who is trying to dominate the world, and his ally Ardala. Buck’s cohorts are the genius Dr Huer, Wilma and her younger brother, Buddy.

By 1932, when the spin-off radio serial was launched, Buck memorabilia crammed the bedrooms of American boys. Hundreds of thousands of people tuned in to listen to the adventures of the space hero four times a week, whose gadgets and gizmos were simulated on the airwaves by the clever use of power tools (his psychic disintegration ray was an electric razor, for example). Buck Rogers was, in all ways, a household name.

In 1939 Buster Crabbe, who had played Buck’s imitator Flash Gordon, donned the robe of the time-displaced adventurer for a cinema serial. This Buck’s origin stepped up the science fiction wow-factor – he is flying a dirigible with his colleague Buddy (changed from his earlier role as Wilma’s brother) when they go down over the Artic. The ship is carrying an experimental gas, Nirvano (a shameless piece of McGuffin pinched by ITV’s poor 1999 drama The Last Train). The pair are instructed to inhale the gas in order to preserve their lives. Of course, when they wake up, they’re not in early 20th century Kansas any more, so to speak. This serial – of the kind that ran before the main feature in the days before televison – had Buck and Buddy revived in 2440. Killer Kane is again the villain, this time at the head of a band of super-gangsters which rule the Earth. Buck joins the freedom fighters, and, in a complicated plot, seeks aid from the planet Saturn. The 12-parter was recycled endlessly, being cut together for a 1953 film release, Planet Outlaws and edited again for television in 1953 in the shape of Destination Saturn. It even ran in the ’70s and ’80s on British TV. Though virtually indistinguishable from the Flash Gordon serial, it was far more polished than other SF offerings of the time, and had a kind of muscular vitality the ’80s version lacked. The wiry Buster Crabbe, an athelete, was a world away from the toothy avuncularity of Gerard.

The TV show that followed in 1950 was, by all accounts, a disappointment, though it is difficult to gauge as there are reputedly no copies of this long-forgotten piece of TV history. It was only the second ever TV SF show after all (the first being Captain Video and His Video Rangers), and the signature elements of Buck Roger’s universe, the constant action and clever gadgets, were severely hampered by the static, live nature of television.

The TV show finished in 1951, and Buck went into a slow decline. Nowlan had long left the comic strip behind, and it lost much of its power. Though it ran until 1967, it was confined to but a few newspapers. “Buck Rogers”, once a commonplace synonym for all that was futuristic in the speech of Americans, became a derogatory phrase applied with the same level of disdain as someone might have said “Doctor Who monster” ten years ago.

There was no Buck for 12 years, until maverick producer Glen A Larson got his hands on the property, launching a new

Buck onto an unsuspecting public in 1979. Many of the main elements of the story remained wholly intact, but the concept was retooled for the age of disco. “The original space man! The ultimate trip! Buck Rogers swings back to earth and lays it on the 25th Century!” screamed the jive-talking tagline. But disco was not the only innovation since Buck had last entertained the masses – feminism had come along in the meantime and grabbed the world by the proverbials. In response to this, Deering was promoted to Colonel, (though the character was always in need of rescuing and actress Erin Grey had to a) Dye her hair blonde and b) prance about in a shiny catsuit – feminism was yet to be fully integrated into the popular consciousness) and had an arch relationship with Buck with more than a hint of “mother knows best” to it. Ardala too was given preminence over Killler Kane, who was reduced from emperor of the world to henchman. She was now a sexually bored yet ultimately dangerous Princess, daughter of King Draco, evil overlord of one of Earth’s antagonistic ex-colonies. Again, empowered as actress Pamela Hensly was, Ardala was required to prance around in a whole range of adolescent-bothering outfits. Not that this upset Gerard, who had the pair of these lovely, self-determining chicks fighting over him in the show.

“All those beautiful women were one of the reasons I had such a good time doing it! It was in my contract ‘scantily women only’. We were kind of kinky, a little ahead of our time,” He told SFX in a 1999 interview.

Originally intended as a pilot for a TV show, Buck Rogers went on general theatrical release in the US where it tapped into the public’s fondness for the character, grossing vast amounts of cash.

“The figures are burned into my mind,” Gerard told us, figures tripping off his tongue as he recounted his glory hour. “It took 35 million in one month, before being removed from screens because it had been pre-sold to cable. It was one of Top 5 grossing pictures in 1979. In the opening weekend alone it took 12 million dollars, and this was three dollars a ticket at the time.”

(These big figures, predictably, prompted the third re-release of the old Universal Buster Crabbe serial).

Feminism's advent had a minimal impact on the new Buck Rogers. The last Wilma might have been a capable colonel, but men were encouraged to look at her tightly clad backside.

And what marvels! Actually, no. The keyword with Buck Rogers’ 80s incarnation is ‘fun’, and that in the lightest sense. Behind the recycled, unused Battlestar Galactica concepts (another Larson show) and Ralph McQuarrie spaceships, the stories suffered from the curse of syndication – the need for the series to be shown in any order at all cut out any character development or story progression, with many narrative inconsistencies between episodes. The future looked like a bad nightclub furnished by early Ikea, so soulless and plastic that when Buck paints faces on his furniture many viewers must have empathised. But the show illustrated one important social shift – the idea of relentless social progress through science had taken a beating, and it was often Buck’s knowledge of the old ways that got him out of scrapes. This aside, the show relied heavily on comedy, particularly from Twiki, Buck’s mentally deficient midget robot sidekick, and this did not make for the gut-wrenching tale of one man lost across the centuries. Even when the film tried to capture this aspect of Buck’s character, when he sneaks out of New Chicago to his ex-girlfriend’s grave, it slips into pathos.

Worse was to come. Glen A Larson had become little more than a name in the credits once the film had aired, and, as much of a magpie as he was when it came to other’s ideas (Gerard affectionately called him a “bandit”) the TV series lacked his screwball creative energy, and Gerard allegedly argued with the chief writers on the project. Then came the second series…

Where the first series was goofy but fun, the second was risible. Buck joins the crew of the Searcher, a spaceship commissioned to search out “the lost tribes of man”. The first series’ bible made much of Earth’s relationships with her former colonies, though these were never satisfactorily explored, but this level of plagiarism from Battlestar Galactica, was too much. The second season retrod old western and Star Trek plots. Mel Blanc, the cartoon genius who had voiced Twiki in the first series, was replaced by Bob Elyea for much of the second series, to fans’ mystification and outrage, and the little bot’s limelight was stolen by Krichton, an awful robot who owed much of its ancestry to a standard lamp. Buck wasn’t the only anachronistic throwback on board either, a bemused Wilfred Hyde White was wheeled onto the show to stammer and dither his way through awful lines, in a cardigan! Not very sci-fi. Gerard rages against this new direction.

“Our new producer John Mantley had no idea, one of his ideas was to replace Mel. A complete rip off of Star Trek was another. We ditched all those classic characters – Ardala, Killer Kane, the Tigermen. I was saying ‘Look, I’d really like Buck to stay on Earth. Why would he want to leave? He’s been gone for 500 years. The man needs to look around for a while, not go flying off again. John Mantley did not know what he was doing. He did the last part of Gunsmoke. To hear him tell it he reigned during the headier days of Gunsmoke, but he simply presided over the demise of that and the demise of Buck Rogers. He actually bragged about the fact he ripped off one of his Gunsmoke scripts for the Hawk episode. He actually bragged about it, he thought it was really funny that he cast Barbara Luna in both roles – she was the Indian princess and she was Hawk’s wife. The thing is, to actually laugh about it, to have so little respect for the audience, as to say, fuck ‘em”

The audience got the message, and deserted the show in droves. It was canned. Buck disappeared from the popular awareness, only an RPG, published in the late eighties, keeping his memory alive.

But his tale is perennial one, that of a man out of place, in a new world that presents many opportunities as much as it makes him yearn for that which he has lost. With TV SF reaching new levels of sophistication, perhaps it is time for some enterprising producer to take up the torch of Buck Rogers, and carry it once more to light the darkness of the future for us all.

Alex Olson - 21st Century Modernism

Frieze

October 26, 2012

Alex Olson’s paintings are less decorous than they seem at first

glance. In fact, high drama is often hidden behind their moderate scale,

formal elegance and sense of containment, which belie how assertively

her work wrestles with paint as both material and sign. Marks that seem

familiar quickly become unfamiliar; colour functions in surprising ways.

Her paintings also suggest a conflicting array of actions that include

spreading, pouring, wiping, scraping, abrading and sponging, but also

writing or leafing through books.

In previous works, Olson overlaid scrawled grids or fields of cursive marks or scratches with radiant splotches, graphic squiggles and flat areas of paint. Something different was going on in the paintings in her most recent show ‘Palmist and Editor’, which featured varied pairings exploring tensions between contradictory ways of presenting or interpreting information; this syntactical gamesmanship extended to interplay between the paintings. The show’s title suggested both an expansion of possibilities and a paring down – as well as the textured lines of the palm and the smoothed-out lines of text associated with editing – and similar disjunctions were at work throughout the show.

The paintings hung nearly flush with the walls, on thin stretchers, directing attention to the surfaces of the works, which could be read in various ways. Olson uses mundane, even crude, tools – palette knives, window scrapers, cheap brushes – to create discrete layers of alternately delicate and emphatic indexical marks. Some works are built on a layer of paint textured with allover brushstrokes or swirls that recall the patterns on cheaply plastered ceilings. The paint Olson then applies either delicately stains the grooves or sits atop it in a thick, opaque layer. Relay (all works 2012), one of the larger works in the show, initially suggests two elegant decorative columns of blossoms or birds, but the feathery shapes are simply areas of paint that seem to have been sponged on – or sponged on and wiped off – over the textured ground.

In the more comical Divulge, a wide pinkish band with wavy sides like the cartoonish result of a huge tool dragging paint down the canvas at an angle, is layered over a charcoal-grey ground textured with allover spirals. If flesh, or silly putty, could be squeegeed onto a surface, it might resemble this emphatic pink shape. Divulge is one of several paintings in which Olson has neatly applied thick swathes or stripes while leaving a messy edge. It’s as if with the same gesture she’s depicting a brick and the cement oozing beneath it: both stasis and movement, solid and liquid. In Place, wide blue and white lines made with a palette knife – leaving a ridge of paint where the knife was lifted from the canvas – create a Rothko-esque composition: a larger rectangle formed of white marks stacked on a smaller one formed of blue marks, on a tan ground. The ground also evokes aged paper, just as the jaunty arrangement of lines somehow recalls mid-century illustration, making the lines’ heft all the more startling.

In Place and other works in the show, high Modernist painting seemed to be a distant touchstone. Palms for an Editor suggests a muted echo of work by Barnett Newman – with red layered over blue in a stripe down the centre of the canvas, against a mottled grey background – although the scale is closer to that of a reproduction in a lavish coffee-table book and the motivation entirely different. In all of Olson’s work it’s as though surfaces have been placed under a spotlight to better allow them to be read, interpreted and speak to one another.

-Kristen M. Jones

In previous works, Olson overlaid scrawled grids or fields of cursive marks or scratches with radiant splotches, graphic squiggles and flat areas of paint. Something different was going on in the paintings in her most recent show ‘Palmist and Editor’, which featured varied pairings exploring tensions between contradictory ways of presenting or interpreting information; this syntactical gamesmanship extended to interplay between the paintings. The show’s title suggested both an expansion of possibilities and a paring down – as well as the textured lines of the palm and the smoothed-out lines of text associated with editing – and similar disjunctions were at work throughout the show.

The paintings hung nearly flush with the walls, on thin stretchers, directing attention to the surfaces of the works, which could be read in various ways. Olson uses mundane, even crude, tools – palette knives, window scrapers, cheap brushes – to create discrete layers of alternately delicate and emphatic indexical marks. Some works are built on a layer of paint textured with allover brushstrokes or swirls that recall the patterns on cheaply plastered ceilings. The paint Olson then applies either delicately stains the grooves or sits atop it in a thick, opaque layer. Relay (all works 2012), one of the larger works in the show, initially suggests two elegant decorative columns of blossoms or birds, but the feathery shapes are simply areas of paint that seem to have been sponged on – or sponged on and wiped off – over the textured ground.

In the more comical Divulge, a wide pinkish band with wavy sides like the cartoonish result of a huge tool dragging paint down the canvas at an angle, is layered over a charcoal-grey ground textured with allover spirals. If flesh, or silly putty, could be squeegeed onto a surface, it might resemble this emphatic pink shape. Divulge is one of several paintings in which Olson has neatly applied thick swathes or stripes while leaving a messy edge. It’s as if with the same gesture she’s depicting a brick and the cement oozing beneath it: both stasis and movement, solid and liquid. In Place, wide blue and white lines made with a palette knife – leaving a ridge of paint where the knife was lifted from the canvas – create a Rothko-esque composition: a larger rectangle formed of white marks stacked on a smaller one formed of blue marks, on a tan ground. The ground also evokes aged paper, just as the jaunty arrangement of lines somehow recalls mid-century illustration, making the lines’ heft all the more startling.

In Place and other works in the show, high Modernist painting seemed to be a distant touchstone. Palms for an Editor suggests a muted echo of work by Barnett Newman – with red layered over blue in a stripe down the centre of the canvas, against a mottled grey background – although the scale is closer to that of a reproduction in a lavish coffee-table book and the motivation entirely different. In all of Olson’s work it’s as though surfaces have been placed under a spotlight to better allow them to be read, interpreted and speak to one another.

-Kristen M. Jones

Walker Art Center Blog

October 5, 2012

In this series of online studio visits, the 15 artists in the upcoming Walker-organized exhibition Painter Painter respond

to an open-ended query about their practices. Here Los Angeles–based

artist Alex Olson converses with exhibition co-curator Eric Crosby.

Eric Crosby

To begin, let’s start with appearances. Whenever I encounter one of your paintings, I learn something new about paint—its materiality, its consistency, its presence as image and surface. What is paint to you, and how do you describe your use of it.

Alex Olson

I’d say there are two main qualities of paint, specifically oil paint, that especially appeal to me. One is its enormous range as a material. Depending on how it’s applied, it can read from graphic to visceral. Most of my paintings take full advantage of this quality, incorporating a variety of tools and marks to arrive at the finished piece. The second quality is its extensive history. It’s impossible to make a mark at this point that doesn’t come with a historical referent, but this is actually a huge benefit. You can pull from art history’s enormous catalogue and build off of a past meaning, re-situating it in the present toward a different end. In doing so, it’s important to understand how a specific mark or idea functioned in the past versus now, and to consider what using it now would mean, but this creates even richer possibilities to choose from.

Eric Crosby

To begin, let’s start with appearances. Whenever I encounter one of your paintings, I learn something new about paint—its materiality, its consistency, its presence as image and surface. What is paint to you, and how do you describe your use of it.

Alex Olson

I’d say there are two main qualities of paint, specifically oil paint, that especially appeal to me. One is its enormous range as a material. Depending on how it’s applied, it can read from graphic to visceral. Most of my paintings take full advantage of this quality, incorporating a variety of tools and marks to arrive at the finished piece. The second quality is its extensive history. It’s impossible to make a mark at this point that doesn’t come with a historical referent, but this is actually a huge benefit. You can pull from art history’s enormous catalogue and build off of a past meaning, re-situating it in the present toward a different end. In doing so, it’s important to understand how a specific mark or idea functioned in the past versus now, and to consider what using it now would mean, but this creates even richer possibilities to choose from.

art ltd.

July 1, 2012

Painter Alex Olson contributes five works to the biennial

that reach equally into the archives of AbEx and Minimalism, sparking a

lively dialogue between the two. Olsen received her BA from Harvard and

subsequently studied at CalArts, where she received her MFA in 2008; her

practice combines additive and subtractive processes--impasto,

sgraffito; sgraffito, impasto--suggesting a synthesis of her bicoastal

education with a leaning towards historic influences. In her previous

body of work, she explored abstraction with a Twombly-esque edge: a

persistent scrawling relief scratched into the surface of her works

ranging from a misshapen modernist grid to chaotic scrawling lines

overlaid with thick patches of paint. Two of the works seen at the

Hammer, Proposal 1 and 3 continue

that explosive energy with bright multi-colored graffiti, while the

others seem to have found a means of control without any measurable loss

of passion. In Proposal 2, a transcendent

white-on-silvery-white creation evoking equal helpings of James Hayward

and Mary Corse, revels in pure luminosity. At the end of the lineup, Proposal 5,

a curved stripe runs off the upper edge of the canvas, painted in a

striking peach-on-charcoal combination, suggesting the infinite

expansion of space and possibilities left open to explore.

-Molly Enholm

-Molly Enholm

Interview Magazine

August 20, 2010

Once upon a time, in the 1960s, if you were a "good" painter,

according to contentious critic Clement Greenberg, you made abstract

works with big block of color and a little bit of shading to acknowledge

that no matter how hard you try, there's still always some sense of 3-D

illusion involved when pigment gets on canvas. Half a century later, a

"good" artist makes no fuss about a painting's status as an object.

Which is why 32-year-old Los Angeles-based painter Alex Olson finds

herself in the middle. "My paintings have to do with how you read

surfaces," the CalArts graduate says, referring to her groups of works

on very thin stretchers that aren't quite a series but "a giant

conversation among paintings, some of them louder than others." If her

paintings could talk, they'd speak of recurring, very basic shapes, and

thin brushy oils. "They're of an abstract vernacular but with loads of

signification," Olson says of the deceptive shadows under her flat

painterly patterns. Olson makes her solo New York debut at Lisa Cooley

gallery on September 1.-Alex Gartenfeld

Back to the Future and the Impossibility of Tracing the Present

How Time Travel Works (and doesn’t) in Back To The Future

Arguably,

no movie involving time travel can ever actually make sense in the

realm of continuity. I have to give tremendous credit to the Back To The Future

writers for taking it on in the first place. This series has it all:

paradox, parallel timelines, and altering history both past and future.

Arguably,

no movie involving time travel can ever actually make sense in the

realm of continuity. I have to give tremendous credit to the Back To The Future

writers for taking it on in the first place. This series has it all:

paradox, parallel timelines, and altering history both past and future.As an audience, we all cope with the discrepancies in different ways. Some of us rationalize the impossible because it’s the only way we can enjoy the reality presented to us. (Have you seen Heroes this season?) Some of us believe wholeheartedly in “suspension of disbelief” and are all too understanding of the limitations of Hollywood (Ross, Joey, and Chandler love the Die Hard films, yet they don’t hesitate to accept Bruce Willis when he shows up on Friends as a guest character). And then there are those of us who just unconditionally believe everything we see and hear. [Not on this site. —Ed.]

For those of us who will never be satisfied without a little digging, I present the following theories.

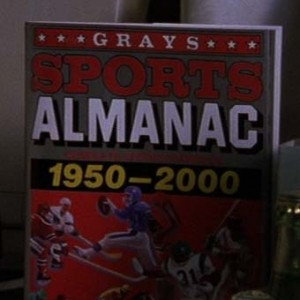

We’re all familiar with this example of a paradox because it drives the plot for Part 2: As Marty and Doc are distracted in the future, old Biff steals their time machine and goes back in time to hand his past self a sports almanac. This creates a paradox that even Doc Brown himself admits could be disastrous, since a person interacting with him/herself in the past or future could destroy the universe.

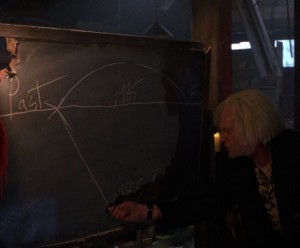

Traditional Timeline Theory

Doc Brown’s revelation implies that he subscribes to traditional timeline theory, in which there exists one single timeline. Not being a member of clergy, I can’t speak specifically to what in life could actually trigger an apocalypse, but I do agree that Doc presents a major paradox: According to this theory, old Biff should be creating memories for himself at the exact same time he speaks to his younger self, which could be disconcerting to say the least.

Furthermore, by handing himself that book, he is altering young Biff’s path so significantly that old Biff should have a completely different personality. For one, young Biff now becomes extremely rich and powerful which would make anyone a different person in the future; and for another, this new Biff probably doesn’t have a reason to go back in time and hand himself the book in this newly created future, thus severing the circle of time.

Predestined Timeline Theory

He walks the line.

For example, when Marty and Doc travel back in time and discover Biff’s alternate reality, this is a temporary tangent, not the “final” timeline. Ultimately, Marty does recover the almanac from young Biff and restores his original reality.

Even though Marty doesn’t save the day until the end of the movie, this certainly doesn’t mean that it hasn’t already happened in the “predestined” timeline. We don’t follow old Biff’s story once he returns to the future, but his plan could have already failed, assuming the predestined timeline prevails.

Displaced Timeline Theory

That's just bad compositing. Oh, also it's a rip in the space time continuum in the process of being "reset."

Apparently, the answer is in the eye of the beholder. Only our heroes, the time travelers, are aware of the transition. (Why doesn’t Marty have any memory of his new past?)

This brings us to the theory of a displaced timeline, in which we assume that a significant change in the fabric of time will cause it to rip. In order to heal itself, it must reset to allow for this alteration. This “reset,” however, takes time (as evidenced by Marty slowly being erased from existence in Part 1), suggesting that the time travelers have a chance to “repair” the altered fabric before it resets.

Following this thinking, if Marty and Doc had taken too long to retrieve the almanac from young Biff, their memories would have reset to the new “healed” timeline (where Marty is Biff’s stepson and Doc has been committed). Sadly, this theory hits a snag here – what happens when there are multiple time travelers at once? I’m not even going to begin to pretend that I can wrap my head around that one. Puzzle it out in the comments, if you can.

Tapestry Timeline Theory

Let’s

think outside the box. Let’s say that life is a “tapestry” of time,

with various threads moving about in different directions, sometimes

converging, but never traveling along one straight timeline.

Let’s

think outside the box. Let’s say that life is a “tapestry” of time,

with various threads moving about in different directions, sometimes

converging, but never traveling along one straight timeline.When old Biff travels back in time, he could actually jump to another thread and create an alternate reality different from his original reality. Marty and Doc don’t notice the difference until they travel back in time and discover the altered thread in their originating time.

This theory offers an explanation for why the entire world doesn’t change around Marty and Doc in the exact instant that Biff disappears in the stolen time machine (as it would on a single timeline), and why Doc believes it would be fruitless to return to the future once they’d traveled back in time and discovered what Biff had done.

I don’t think that the writers of Back To The Future took any theories into consideration beyond traditional, and since traditional theory is flawed, I can only assume that they hoped suspension of disbelief would fill in the gaps. I can’t really blame them, because after all Back To The Future is a family movie aimed at the more casual time traveler.

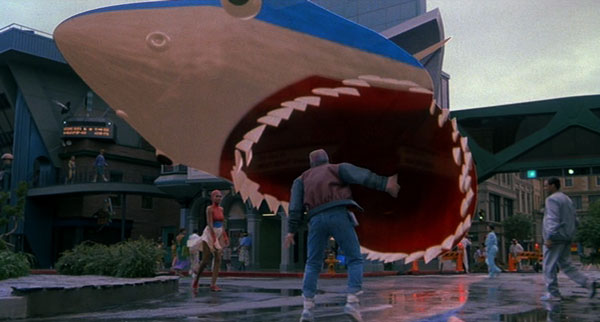

With all the paradox, altered realities, and suspension of disbelief, why then are we able to smile and love this series? I guess because it’s awesome. Honestly, the only real travesty is that it is now closer to 2015 than 1985, and we don’t have hoverboards, or movie posters replaced by giant holographic sharks.

Marty lives every week like it's Shark Week.

Sterling Ruby I - Back to the Future

London – Sterling Ruby at Hauser and Wirth Savile Row Through May 4th, 2013

May 3rd, 2013

Sterling Ruby, THE POT IS HOT (2013), via Hauser and Wirth

Los Angeles-based Sterling Ruby is currently exhibiting a selection of new works in London, on view at Hauser and Wirth’s Savile Row location. Investigating a creative process that incorporates studio detritus and recycled elements of previous work into his assemblages and collages, Ruby welcomes a new perspective on the fixed artwork.

Sterling Ruby, EXHM (Installation View), via Hauser and Wirth

Utilizing pieces of pottery, paper, photographs, and other cast-off materials, Ruby explores the practice of art making as that of constant flow and reconstitution. For EXHM, his adaptation of the word “exhumation,” the artist works at the physical rebirthing and repurposing of fragments and failed pieces. Pieces are fixed together using spray paint and adhesive, joining various leftovers from the studio environment into textured, layered works that play on ideas of decay and process in the creative cycle. Ruby’s process throughout these works seems informed by notions of sustainability, keeping materials and small fragments of paper on hand until they find their proper home on a work.

Sterling Ruby, BC (3935) (2012), via Hauser and Wirth

Ruby’s Basin Theology is a perfect example of this process, a series of works in which the artist continually reglazes and refires shards of pottery from past works, creating dense pieces that show the traces of their ongoing growth and change. The work seems to constantly be in motion, and could continue infinitely, but stands complete because the artist decided that he was finished. In other, larger works, Ruby pursues a sort of post-apocalyptic assemblage, displaying enormous blocks of wood soaked in patriotic colors, evoking a bizarrely presented sense of comic foreboding. His MONUMENT STALAGMITE is of particular note here, a towering fragment of wood and paint, with the semantically potent inscription “We Luv Strugglin’” painted on its side.

Sterling Ruby, VAMPIRE 104 (2013), via Hauser and Wirth

A tangible sense of mysticism, or rather, ritualism, seems to pervade the exhibition. Titles alluding to death and rebirth, and rhetorics of redemption complement the process detailed throughout the show. Ruby paints for himself a role as benevolent creator, rescuing material from demise to be reused in his works.

Sterling Ruby, EXHM (Installation View), via Hauser and Wirth

Despite his assumed position as creator, or rather, re-animator, Ruby’s work in EXHM also works at the idea of art as context. Instead of digging within the work and the materials used, the artist embraces the found or encountered as elements of his work, defined by the space in which his piece is situated, and the particular affects of the work for the artist. Relations between the artist and each piece are immediately foregrounded, and Ruby’s position shifts from an autonomous, active authority to a willing participant in the art process, relaying his own impulses towards materials as he places them in juxtaposition with others.

EXHM is on view until May 4th.

Sterling Ruby, SPCE (4023) (2012), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby, Monument Stalagmite:WE LUV STRUGGLIN’ (2013), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby, EXHM (Installation View), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby, EXHM (3915), (2012), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby, EXHM (Installation View), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology:MMP-3FDDKG (2012), via Hauser and Wirth

Sterling Ruby II

The works in ‘EXHM’ are acts of autobiographical, art historical and

social archaeology. Ruby has turned inward, treating his studio as an

excavation site where discarded, buried and collected artworks and

materials are dug up and reanimated. These new series highlight Ruby’s

continued subversion of both material and content. They reveal a

therapeutic process that embodies a site between creative utility and

futility through the recycling of studio ephemera and misfired ceramic

works.

In his recent ceramics, collectively titled ‘Basin Theology’, Ruby fills vessel-like forms with fractured pieces of his discarded ceramic work. The reuse of broken remnants becomes symbolic of an unburdening, a redemption of past mishaps and failures. The ceramic fragments, often resembling animal remains or pottery shards, are melded together through a process of repeated glazing and firing. The more times they are fired, the thicker and more vivid their glaze becomes, and the more charred and gouged the surfaces appear.

‘CDCR’, a large, poured urethane sculpture in the colours of red, white and blue reconfigures the artist’s ‘MONUMENT STALAGMITE’ sculptures. ‘THE POT IS HOT’, with its mortar and pestle-like form, is reminiscent of the artist’s earlier ceramic works.

When making poured urethane sculptures like ‘CDCR’, Ruby lays down pieces of cardboard to protect the studio floor. His EXHM collages take these cardboard pieces covered in urethane, dirt and footprints and reinvent them as formal compositions, which Ruby finalises by inserting pictures of burial grounds, correctional facilities, prescription packages and other objects found around the studio.

Ruby’s fabric collages, the BC series, repurpose rags, fabric scraps, and clothing that are then applied to a ground of bleached black denim. The fabric echoes the playful patterns of traditional quilts, specifically the quilts of Gee’s Bend, and the pop-like works of Rauschenberg or the formal compositions of Malevich. Both Ruby’s BC and EXHM series inhabit an interstitial space between painting and craft; industry and waste.

Ruby’s soft sculptural works will hang from the ceiling of the North Gallery, falling down into a pile on the floor. In the South Gallery, Ruby’s gaping vampire mouths line the walls; single pillowy droplets of blood cling to each fanged tooth. Ruby’s soft works take objects of comfort, such as blankets and quilts, and mould them into threatening forms, which are at once aggressive and playfully cartoonish.

In his recent ceramics, collectively titled ‘Basin Theology’, Ruby fills vessel-like forms with fractured pieces of his discarded ceramic work. The reuse of broken remnants becomes symbolic of an unburdening, a redemption of past mishaps and failures. The ceramic fragments, often resembling animal remains or pottery shards, are melded together through a process of repeated glazing and firing. The more times they are fired, the thicker and more vivid their glaze becomes, and the more charred and gouged the surfaces appear.

‘CDCR’, a large, poured urethane sculpture in the colours of red, white and blue reconfigures the artist’s ‘MONUMENT STALAGMITE’ sculptures. ‘THE POT IS HOT’, with its mortar and pestle-like form, is reminiscent of the artist’s earlier ceramic works.

When making poured urethane sculptures like ‘CDCR’, Ruby lays down pieces of cardboard to protect the studio floor. His EXHM collages take these cardboard pieces covered in urethane, dirt and footprints and reinvent them as formal compositions, which Ruby finalises by inserting pictures of burial grounds, correctional facilities, prescription packages and other objects found around the studio.

Ruby’s fabric collages, the BC series, repurpose rags, fabric scraps, and clothing that are then applied to a ground of bleached black denim. The fabric echoes the playful patterns of traditional quilts, specifically the quilts of Gee’s Bend, and the pop-like works of Rauschenberg or the formal compositions of Malevich. Both Ruby’s BC and EXHM series inhabit an interstitial space between painting and craft; industry and waste.

Ruby’s soft sculptural works will hang from the ceiling of the North Gallery, falling down into a pile on the floor. In the South Gallery, Ruby’s gaping vampire mouths line the walls; single pillowy droplets of blood cling to each fanged tooth. Ruby’s soft works take objects of comfort, such as blankets and quilts, and mould them into threatening forms, which are at once aggressive and playfully cartoonish.

Death and the Alienation of Repetition

A quarter century after Andy Warhol’s death, his work resonates more than ever. Several museum exhibitions are focusing on his influence in painting, photography, film, performance, and more

Deborah Kass, 16 Barbras (The Jewish Jackie Series), 1992,

Few artists are so eager and able to accurately assess their legacy, but there is something eerily prescient about Warhol’s grainy conception of death. His machinery, it seems, is still very much ticking away. His themes, processes, personas, and approach to making art are evident in everything from the ready-mades and Pop portraits of his direct descendents to the work of some of the most boundary-pushing conceptualists, abstract painters, and video artists working today.

With his Factory, his Marilyns, his films, and his many riffs on banality, seriality, and kitsch, “Andy knocked down obstacles that no one ever thought about before,” says critic Arthur Danto, who has written extensively on Warhol’s work. “What Andy did is far more innovative than anything else I can think of. Andy did commonplace things, and yet he did them in a way and in a number that has nothing really quite like it. Everything he did was different.”

Which is why 50 years after his public debut and 25 years since his untimely death, Warhol remains, some would argue, the major touchstone for contemporary art. “He’s like Picasso in the sense that you just don’t run out,” says Jeffrey Deitch, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. “He has become one of the most influential people in all of contemporary culture. You see the influence in painting, sculpture, performance, photography, film, even journalism. Life as performance, life as art, reality TV—it’s all Warhol’s world.”

Several recent exhibitions have taken up the charge as well, most notably this fall’s blockbuster-scaled “Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years,” opening September 18 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which will travel to the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh next year. The works on view span several generations and nearly all media. They demonstrate the wide variety of ways in which artists have ingested Warhol’s politics, practices, and Pop-friendly fixations and spit them out to express new zeitgeists, new anxieties, and candidly personal points of view.

In “Regarding Warhol,” the artist’s soup cans and Brillo boxes have given way to Coca-Cola-emblazoned Neolithic urns by Ai Weiwei, as well as Tom Sachs’s luxury-branded weaponry, and Damien Hirst’s bountiful cabinets of prescription drugs. Warhol’s Marilyns, Jackies, and Maos have been recast as Maurizio Cattelan’s topless supermodel-turned-art-collector Stephanie Seymour, Elizabeth Peyton’s elegiac renderings of Kurt Cobain, and Luc Tuymans’s steely depiction of Condoleezza Rice. And the Factory has been mirrored in the production methods of Neo-Pop masters, like Takashi Murakami and Jeff Koons.

The loan-heavy exhibition stemmed from a sentence that cocurator Mark Rosenthal says he kept encountering in conversations, articles, and books: Warhol is the most important artist of the last 50 years. “I thought it would be kind of amazing to see what that looks like,” he says. “He’s with us whether you love him or hate him, and in so much of the work that’s been produced since. Because of Warhol, everything changed.”

“Certain people bend the course of art history,” agrees Chuck Close, whose 1969 Phil, a colossal rendering of composer Philip Glass, is in the show. “Somehow, they deflect it from the direction in which it was going and send it off somewhere new,” Close continues. “They make something so surprising that it doesn’t look like art.” Until, eventually, what they’ve made starts to define it.

Warhol’s most obvious legacy is his astute appropriation of mass-produced products. Of course, he was not the first artist to use everyday imagery and ephemera in his work. He was predated by Marcel Duchamp, with his ready-mades, and then Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who, in the late 1950s, were estheticizing and recontextualizing objects from their everyday lives. But Warhol’s hard-edged, brand-savvy, serial approach was quite different.

“For me, the art world in the 1960s really broke down into two notions about figuration,” Close says. “There were those people who were trying to breathe new life into what was essentially 19th-century portraiture versus those people who were intent on making a truly modernist form of figuration.” Warhol, he adds, really “kicked the door open for an intelligent, forward-looking, modern kind of painting.”

The trajectory begins in 1962. It was the year of the first Coca-Cola bottles, the first soup cans, the first Marilyns, and Warhol’s groundbreaking exhibitions at the Ferus gallery in Los Angeles and the Stable Gallery in New York. Reverberations were felt throughout the art world almost immediately. Whether his contemporaries realized it or not, something was, indeed, in the air.

Edging toward banality themselves, John Baldessari and Ed Ruscha immortalized their local gas stations in the mid-’60s and Vija Celmins made photorealist paintings of catastrophic imagery pulled from the news, shortly after Warhol debuted his own “death and disaster” series. “I don’t know whether Andy Warhol was so much an influence,” she told “Regarding Warhol” co-curator Marla Prather in an interview to be published in the exhibition catalogue. “But, in retrospect, I can see that . . . his influence must’ve been everywhere.”

Indeed, by the 1970s, Warhol was a household name whose factorylike take on fine art prefigured current studio practices and today’s staggering market demands. But his singular approach to found imagery and appropriation also set the stage for the Pictures Generation, argues Prather, from Richard Prince’s Marlboro men to Cindy Sherman’s self-styled Hollywood film stills to Louise Lawler and Sherrie Levine’s loaded snapshots of other people’s art. “Appropriation may have been more or less invented by Duchamp,” Rosenthal says. “But it hadn’t really been dealt with much since. Warhol turned it into a movement.”

Rosenthal and his colleagues are also looking at some of the less expected Warholian threads that have populated his intergenerational wake: abstraction, identity politics, and sex. Of the latter, Prather insists, “You couldn’t have Nan Goldin without Andy Warhol.”

Films like Blow Job (1964) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968), as well as the screen-printed Thirteen Most Wanted Men (1964), which cleverly suggested that the FBI’s hit list was somehow akin to Warhol’s own, granted a sort of permission “to come out of the artist’s closet,” she adds. “When you think about artists like Rauschenberg and Johns, that work is much more coded in terms of gay issues and lovers.”

In this sense, Warhol paved the way for photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Catherine Opie. Prather also draws a connection between Warhol and the ambisexual characters in video works by younger artists like Ryan Trecartin and Kalup Linzy.

As for identity politics, Warhol’s famously indifferent demeanor was also famously a front—he loved his mother, he regularly went to church, and, like most of us, he wished he looked like a movie star. It’s a reading of Warhol that Brooklyn artist Deborah Kass spent years tackling in her practice. “I consider Andy’s work to be really autobiographical, very deeply felt, and the opposite of everything he said about it,” says Kass, who is in the Met show and has a major midcareer retrospective opening October 27 at the Andy Warhol Museum.

In “The Warhol Project” (1992–2000) the artist cast her personal icons—most notably, Barbra Streisand—in several Warholian motifs and roles. Streisand appears in a string of tightly cropped, screen-printed profiles, and in a series of paintings, called “My Elvis,” which portray the diva multiplied on canvas in her cross-dressing Yentl garb.

As a Jewish girl growing up on Long Island, Kass explains, “Barbra was the first Hollywood star I could identify with. I loved Marilyn Monroe, I loved Clark Gable, but I didn’t know what I was missing until I saw Barbra—someone who looked like everyone I knew. She was someone who understood the power of her difference and who wasn’t easily absorbed into a male narrative. She was completely aspirational.”

It was a way of identifying with Warhol and “his outsiderness,” she says. In that sense, his style and character became something of a tool. She adds, “I could use it to say what I wanted to say.”

Meanwhile, MOCA director Deitch is leading the way in positioning Warhol as a major progenitor of today’s foremost riffs on abstraction. He mounted a group show at the museum this summer featuring works by a dozen or so contemporary abstract artists—Tauba Auerbach, Mark Bradford, and Wade Guyton among them. Auerbach showed a handful of her acrylic-on-canvas “Fold” pieces—photorealistic renderings of creased and crumpled fabrics that, from a distance, look like abstract tableaux. Bradford presented a series of his signature collages composed of flyers, scraps, and other detritus collected in sociopolitical hot zones like South Central Los Angeles, and Guyton showed several new impressions on linen. Guyton’s cleverly conceived works use an inkjet printer’s inadvertent streaks and hiccups to produce stark, abstract effects.

Titled “The Painting Factory: Abstraction After Warhol,” the exhibition made the argument that many of the most pervasive trends in abstraction today are firmly rooted in Warhol’s work. His screen-printed shadows, his camouflage paintings, and his 1980s renderings of Rorschach blots were all representational endeavors in practice that, on the surface, appear abstract.

“It’s the mechanical approach, the mediation, the ability to embed social or personal content into an abstract image,” Deitch says. “Even though he wasn’t a pretentious philosopher, Warhol was very conscious of his contributions to a new way of thinking.”

Either that, or it’s all just a self-fulfilling prophecy, a posthumous extension of Warhol’s own 15 minutes of fame. As Guyton put it, “It’s like he has a PR firm on retainer after death.”

Rachel Wolff is a New York–based critic, writer, and editor.

Jim Isermann - Compilation of Outdated Trends

Jim Isermann: Utopia Now

By Dave HickeyIn The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, Warhol confides in us his hope that someday he might be able to hire a boss. Andy's desire is worth citing here because, like Warhol (and quite unlike Jim Isermann), most of the artists who blur the boundaries between art and design do so because they too would like a boss. They like the rule-bound environment in which things are designed, the discipline of oversight, the specificity of the assigned task, the rigor of budgets, and the complexities of collaboration. For these artists, in D. H. Lawrence's phrase, the music of freedom is the rattle of chains. For Jim Isermann, freedom is no such thing. When you ask him why he considers himself an artist who exploits the language of design rather than a designer who works in art venues, he will tell you quite frankly that he doesn't work for anyone, that he makes his own rules and does what he thinks needs doing.

Artists, of course, have been saying this for centuries-that they know better and can do better-that they can make a better painting or a better sculpture. Jim Isermann, however, is an artist/designer in the tradition of Giulio Romano and Andrea Palladio. He thinks he can make everything better-that he can make the world better by improving the quality of its objects and surfaces and make the world even better than that by improving it more succinctly, efficiently, and economically than anyone else. These are the disciplines Isermann accepts in lieu of a boss: simplicity, elegance, industry, and economy. Adhering to these principles, he begins most of his projects straightforwardly: with a primary modular unit derived from the vast repertoire of modern design and with a minimal palette of industrial color. For walls and floors, he elaborates these elements through a set of simple algorithmic permutations to generate a pattern of maximum interest and complexity. He applies this pattern to the walls or the floors as they exist using the most economical and efficient means available. In situations where a more ornate surface is required, labor-intensive craft is applied instead of costly materials.

The achieved consequences of Isermann's methodology are invariably ebullient-wide-screen panoplies of saturated color and heady invention that, far from repudiating the rigor of their creation, are invested by that rigor with a cool seriousness about the occasions of human happiness. This, in Isermann's aesthetic, is quite enough. The world can be redeemed and made more joyful in explicable ways through work and thought-and should be-without mystification, waste, or inordinate expense. In practice, Isermann holds to this shade-tree utopianism with a self-assurance bordering on arrogance. He regards any resort to expensive material, "tasteful arrangement," elaborate technology, or architectural intervention as a last resort bordering on moral failure-as a crutch for artists less talented, industrious, and conceptually sound. This, of course, is only to say that Isermann is an artist and not a decorator, but that is worth remembering.

He may traffic in supergraphics and hot pink motel furniture, but Jim Isermann is, first and foremost, a California artist with Bauhaus tendencies, Minimalist agendas, and formalist precedents in the Abstract Classicism of John McLaughlin and Frederick Hammersley. He is also a knowledgeable authority on the field in which he practices. Whatever there is to know about the migration and repatriation of idioms between the domains of high art and popular design in the twentieth century, Jim Isermann knows, and this, in truth, makes him a bit of a sacred monster, at once the scholar/authority on what he does and the auteur who does it-at once the ornithologist and the bird. Unlike other sacred monsters, however, Isermann is always monstrous in the service of joy. His knowledgeable arrogance is always mitigated by the egalitarian generosity of his meticulous oeuvre. The darker attributes of utopian design-its dictatorial narcissism, its intellectual pretension, and imperial grandiosity-are nowhere present in Isermann's work.

This, I suspect, is because Isermann's utopian optimism is less a belief in the promise of a better future than a belief in the promise of optimism and the social benefits of utopian art. In this sense, Isermann's utopianism is essentially domestic, less sanguine about the future than nostalgic for optimism itself as an attribute of quotidian equanimity and domestic decor. As a consequence, when he evokes the ludic, culturally acquisitive, irrevocably artificial atmosphere of postwar American design, he is not reminding us that this optimism was misguided in its expectation of a better future. He is reminding us that optimism, misguided or not, makes the present better. More specifically, since he is actually creating designs and not commenting on the present by showing us pictures of absent designs, he is also making our present better.

Jim Isermann's utopia is local, domestic, personal, and right now. It is where we live, if we chose to live there, and for Isermann, the primary signifier of utopian conditions-of generosity and democracy-is the openhearted commerce of idioms and ideas between high art and popular design. The primal site of this mutual migration, for Isermann, is the 1950s in America, when the streamlined biomorphism of Arp and Miró suddenly began proliferating on rec-room countertops and beer coasters, when the smooth iconography of revolutionary Constructivism began manifesting itself, as if by magic, in sleek, mass-produced capitalist icons, and young beaux-artistes, Op and Pop and Minimalist, began borrowing these idioms back in aid of new and even more insouciant agendas. What Isermann has done throughout his career is to perpetuate this tradition of migration and appropriation, adapting the formal idioms of beaux-arts practice from the 1960s-of artists like Bridget Riley, Donald Judd, and John McLaughlin-to the needs of contemporary design.

What makes Isermann's endeavor art and not design is that he is, for the moment, the only one doing it. He is working on his own authority against the prevailing logic of institutional wisdom, so his work proposes itself to us as an "as if" and a "why not." Prevailing wisdom in the art world holds that "history" stopped around 1968 and that, as a consequence, the centuries-old, accumulative, acquisitive, transformative flow of stylistic appropriation and formal invention ceased in that moment. This discourse was purportedly replaced by a vertically administered, neo-Victorian discourse of narrative pictures and moral critique that is self-consciously and ideologically isolated from the province of commercial design. Jim Isermann's work simultaneously proposes and demonstrates that this may not be the case, or needn't be. It reminds us that even though "history" may well have stopped and the future evanesced, utopian optimism requires neither. Optimism is an attribute of the present that requires no more than a confirming iconography. If such an iconography exists, utopia is now. Why not?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)