Painting in the twenty-tens; where to now? (You can’t touch this!)

Max Olofsson

Kungliga Konsthögskolan (Royal Institute of Art - Stockholm), 2011

Contents

Painting 1

Hypo-cave 2

Utopia / U can’t touch this 3

Painthing 5

Body language 6

Painting is painting. Everything else is everything else 7

Everything else 8

Lost in translation 8

Passion art 10

2-D alliance 10

Conflict of the surface 11

Confusion of origin, mixing of styles 11

Showing 12

Video games 13

Digital painting 14

(K)not related 15

$ 15

Human 16

1

With this essay, I will present to you my distilled (re)definition of painting; what about it that

is important and what is not. These are my opinions – some based on observations, others

on assumptions. I will bring up and do my best to explain: Painthings, the Conflict of the

Surface and Information Painting.

Painting

Painting has been through a notoriously turbulent time during the last century, specifically in

the early years and around the middle. Some artists sought to make the final painting – the

truest, most painterly painting ever conceived of – beyond which there would be no

direction left to take. A long lasting quest during which some artists despaired, and gave up

on painting altogether (e.g. Duchamp, who in the nineteen-teens, as an act of renunciation

of originality of the art-object, presented an allegedly visually indifferent “ready-made” milk

bottle rack as a work of art, which led to a whole new way of looking at art other than

painting. However – since this essay is specifically dedicated to painting – this is something I

will not speak any more of). Others (Tatlin in the beginning- and Judd in the latter half of the

last century) concluded that painting had to evolve and somehow become more than it had

ever been before and consequently added a third dimension, which subsequently made it

something other than painting.

I can’t think of, nor ever hope to find the exact amount of proclaimed deaths of painting, I

am in any case of a diametrically opposite opinion: painting has far from exhausted its

potential, it is nowhere near an end; I would much rather say it can finally begin!

2

I’m not saying it can finally begin to be provocative; I did not set out to write this essay to

trash-talk previous generations of painters, nor to suggest that all of their efforts and

achievements somehow should have ultimately amounted to nothing, it is on the contrary: a

genuinely hopeful statement and a belief that the near future holds great things in store for

the continued evolution of painting, and the beginning of painting as non-object.

Hypo-cave

This paragraph is a hypothetical unfolding of events, a personal take on things – perhaps a

qualified guess would be a fitting description – above an accurate account of history, but

nevertheless it will provide a background story and set the mood. As I see it, back in the

cave-painting days, you took whatever was necessary to make visible to you and to others

your visions and observations. The paint, in itself, was just something that proved to be

much better at staying on the cave walls than any drawing in the sand would stay (untrampled)

in the sand. This improvement of duration facilitated visual communication, as it

could be shown to more cave-pals, and it would stay there. Suddenly an observation and a

painting made one day could be added to a week later, after having seen something new.

Through the use of this aid, more elaborate pictures could be worked on and important

observations could be recorded; knowledge was spread through the gathering and sharing of

images of encounters made in the world. I would assume at this time it had very little to do

with the paint and the current obsession with it, and infinitely much more to do with the

images you could produce.

I would argue that the ideal painting is a painting as a non-object; the recorded vision or

observation in itself. It is an ideal not easily achieved, but well worth striving for. And, I’d

even go so far as to say it is our duty, as painters – as artists – to work hard at realizing the

ideal. For love of tradition and feeling we’re a part of an ongoing writing of history, we can

only do our best to add to the tremendous group effort it takes to keep moving forward.

Through the history of painting, the paint and the object have gained superiority over the

image, to the point where they on their own (wrongly) represent painting. This shift of focus,

3

or perhaps better: this deliberate confusion of definition for the sake of reinvention started

bubbling with cubism, heated up further with the constructivist approach to painting and

reached its boiling point in and around minimalism and other materialistic, objectemphasizing

movements and positions. But no matter how much I may disagree with certain

views, I should make it clear that all of these twists and turns in and of definitions of painting

have been completely necessary for me to reach mine.

Utopia / U can’t touch this

Now this may be romantic, but I’m completely serious: painting is the utopian dream of

being able to extract from within yourself your personal vision, your way of looking at the

world, the observations you think are important and strive to give meaning to, and being

able to show them to others so that they too can be enriched by them. Through it you

demonstrate your will to protect those precious observations and visions from the blight of

time and touch of man, by which I mean the grasp of greed and the desire to own. It is to

render them untouchable, painting them into the world beyond reach, where they forever

remain as the recording of an idea, subject only to eternal longing and continued watching.

The reason I use the word utopia (literally meaning “no place”, or “nowhere”) is because it is

the perfect analogy for painting. As I see it, and would even venture to say understand it,

this is what it was all about from the beginning. Granted, the word utopia and any

ponderings about what the image is or can be arrived in the discussion significantly later

than the painted image came into being, but it is still what one can hope it was all about.

It can never be sullied by ownership in the same sense that physical objects are attainable if

you have sufficient finances for them. It is not something for someone to hold, it is not that

simple – it is beyond that. In today’s society, you want something – you buy it. But the

instant you obtain it, the initial longing – that which got you interested in the first place –

ceases, and it swiftly assumes the role of just another thing in a line of hundreds of objects

you own. There’s this quick fix for every craving, if you have the money. Apart from, as the

Beatles sang: love and – as I would like to add to their statement – painting; you can never

4

reach the vision it holds. To quote another musician, who happened to create the perfect

theme song for painting with his 90’s megahit, Mc Hammer: “U can’t touch this”!

Painting was never about making an object, even when paintings became objects it was still

originally only about making paintings; the object only came into being as a clever invention

of a transport device that made images portable, so you wouldn’t have to abandon them

with the move from your home (cave/palace). This led to a better communication of visual

information as the paintings could travel to new locations and be seen by new eyes. Painting

has, however, become problematically tied to its supporting object, and today random

objects that somewhat resemble paintings are called paintings, when in fact they really are

objects.

I would like here to make a hopefully helpful parallel to music, which is also something we

produce and pass on to a state of being beyond touch. The production of it may, just as

painting, depend on our bodies to play the actual instruments or our mind and hand to

compose it on a computer, but what comes out is something untouchable, unreachable;

utopian. Something created by us human beings by whatever technical means necessary to

communicate beauty/X in one of its most intangible forms. (I put an “X” there since it might

otherwise exclude anyone striving to express something quite different.) And in the end it is

not about the speakers, or the CD-player (or computer) by use of which the recorded music

can be played and heard again and again, they are simply necessary to transmit the original

recording of the composition.

5

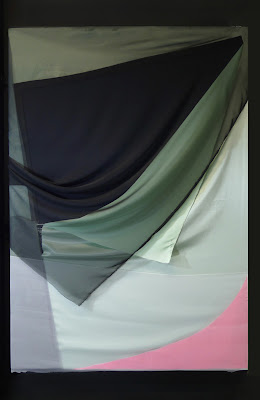

Painthing

If we, for the sake of argument, were to regard painting as a veil – beyond which we cannot

go – with physical painting we can still touch the veil, as it were, and a range of nonsensical

questions are bound to arise from it. And have arisen. Whether the veil itself is made of

fancy cloth (read: metal, cardboard, plastic, etc.), whether it’s thick or thin, heavy or light is

all beside the point – these are concerns belonging to fields other than painting. What is

behind the veil, however; what the “no place” it keeps us separated from looks like, and how

it has been arrived at – stylistically, compositionally and technically – isn’t. When the

materiality of the object confuses or questions the hierarchies of importance, and you don’t

know whether to focus on the probably very delicate and intricate suggestion of a new

flashy carrier of the image, or concentrate on the actual picture, it is, as I have chosen to

phrase it, a painthing. It puts materialistic and physical concerns over pictorial and depends

on a sculptural reading of the artwork.

To give a historical explanation of paintings becoming painthings: Cezanne’s structured way

to paint, his vision of how it should be, and what was then developed by Picasso and Braque

– cubism (or to be precise: analytic cubism) – is all about painting. And it remains so until

material beside paint – worldly things with the purpose of referring to itself, society or

everyday life in a direct, hands-on, materialistic way – is introduced in synthetic cubism.

With the invasion of real space (objects) into painted space, they immediately became

painthings.

I’m not saying painthings are in any way inferior, less worth or trying to make any other

disparaging insinuation, I’m simply stating that they are not so much paintings as they are

something else; the main points of interest lie someplace outside the plane, and a distinction

between the two is necessary to facilitate future discussion about painting. It is difficult to

6

talk about good or bad or well made painting today, when there is no real telling of when it

ceases to be what it wants to be. One painting might have a faint scent of perfume –a subtle

smell of Chanel; another might have been painted with liquid chocolate, and a third may

boast a neat fishbone pattern arrangement of cut up corduroy pants which probably would

be very tempting to touch. My point is, while it all may be very creative and fun and perhaps

even deep and involving, it is not painting. Everything a painting has to say resides within its

two dimensions; it should require no further information. It would be very difficult to say

which one was the better painting since they rely so much on material novelty and randomly

ascribed attributes (e.g. this painting absorbs sound!), whereas the true concerns

(production of fictional space, suggestion of – not physical creation of – a third dimension,

composition, color, etc.) are at most secondary. You are not supposed to smell, eat or touch

it; you’re supposed to look at it!

Body language

Painting, to my mind, has very little to do with the body. Dance, for instance, has very much

to do with it – but not painting. Should anyone insist that painting is like dancing, to me that

would simply be one out of a range of infinitely variable personal processes of painting;

saying painting is dancing is very confusing. What then is dancing, if it suddenly is also

painting? Paintings of a certain size could be argued to have a lot to do with the body, since

they might have been physically demanding to produce, but it is only true for the process of

making and not the visual information it holds, since the same painting could have been

made much smaller. Regarding the physical relation to looking at paintings it is true that a

tiny painting will give a much more intimate and private experience when looked at than a

huge one, which in turn can be imposing on the verge of threatening, and make us feel very

small. But this all has to do with decisions of scale, and is not something that is specific to

painting.

7

Painting is painting. Everything else is everything else

The main reason – should it not be self-evident – for re-defining, and thereby dismissing the

most recently acquired features of painting, is to bring it back to its main constitutive

powers. Before aspiring to merge with or become something else (dance, performance,

installation, sculpture, etc.) it should deal with its own unique intrinsic qualities; the

immediate abstraction from three dimensions to two and the inherent conceptuality of

showing something that isn’t present – whether it is no longer so or it never was.

I would like here to emphasize that I think painting is – and has been ever since its early

conception as a form of communication – a very conceptual idea. It depends on the viewer

to give it space and motion in his or her mind based only on the information it provides. As I

see it, there is little difference between the mental image projected into someone’s mind

through the use of guiding or triggering words, and the one generated by the information

given in a painting. The image is just as untouchable as any meaning of any word; you get

the idea of what it could or should be, but can never get there.

It can only try to overcome its obstacles through its own possibilities. Experimenting with the

third dimension is, as I see it, just an attempt to take a shortcut to making suggested space

real. And that already exists – in everything else. There is a certain beauty in the idea of

dealing with the overwhelming diversity of physical form and texture belonging to the real

world through the soothingly dimensionally limited structure of painting. It is something to

hang on to! To paraphrase Ad Reinhardt, one could put it like this: Painting is painting.

Everything else is everything else.

8

Everything else

Comparing a sound piece, for instance – or a sculpture for that matter – to a painting is quite

strange, as it presupposes a general, all-encompassing communication of ideas, suggesting

all means of expression are equally capable of communicating everything. The horrific

outcome of a fictional – but not unlikely to occur – comparison such as that would inevitably

be something like: “this is a better sound piece than that is a painting.” Looking at and

comparing art based on how interesting the choice of subject matter is and how successfully

the idea is communicated, is lacking something. It lacks a certain care (and by care I almost

mean love) for medium-specific detail, and is judged too broadly on content alone –for it is

not unthinkable that the person who makes the comparison is neither painter, nor soundartist.

I would say it is vital (and I hope I stress it enough by underlining it) that they are

cared for separately, in order to maintain the highest possible quality in each end every

discipline. And they all contribute, each by right of their own unique qualities, to the greater

discourse so that the joint efforts of all disciplines can ascertain a worthy continuation of art.

Lost in translation

Only a small part of the communication a painting produces today takes place in real space –

the room in which it hangs; the rest happens online or via books and magazines. What you

get with the documentation of a painting is a forced re-flattening of the flat surface, and if

the painting originally made a point of its physicality (thickness of paint, specific materials,

e.g. stuff belonging to painthings) the flattening will be ruthless. As a matter of fact, you

might as well call the documentation in that case obliteration of communication, as every

aspect beside the visual information on the picture plane is lost with the documentation:

every physical feature; its materiality, size, weight and texture. But, what’s worse is that not

even the flattest of paintings gets away unaffected. The information it holds will too be

transformed to pixels on screens, and the painting is lost in translation.

9

One could argue that with physical paintings, one thing that still is digitally unmatched is the

precise control of color. While it becomes problematic the very moment you decide to try

and document it – as you face in that instant the same problems of varying color experience

as with digital painting – there is at least one version that is exactly as you want it or left it.

This, however, is of course only viable in ideal, never changing, lighting conditions – which

means it has to stay in one place and also that you can’t document it without first of all

flattening it once more and also losing ultimate control of color.

I’ve mostly looked at images online, in books or seen them as slides. (The “history of slides”,

as Chuck Close very aptly put it about art history, in a conversation moderated by curator

Anne Umland at MOMA, on august 8th, 2007, in conjunction with the exhibition held at that

time called What Is Painting? Contemporary Art from the Collection.) His witty remark hits

the nail right on its head – many times you never get to see the real painting, the unique

object, because it is stashed away someplace safe, or in somebody’s home. Of course there’s

always the possibility it’s hanging in a museum somewhere, but that still might not exactly

be in your vicinity. My point is I’ve seen documentation of paintings far more than I’ve seen

real paintings, and when, on occasion, I go to see the real things I sometimes get a little

disappointed. It troubles me to realize they often have a specific physicality, and angers me

to see there are sometimes little tricks to them; features you would never have guessed

from looking at documentation. There are details suggesting that seeing the object is better

than seeing the documentation; things that seem to underline that the image was not

enough, there had to be some little twist to it.

Imagine painting that has learned to adapt to slideshows and the internet: that in itself

already is its own documentation, painting that finally is all about itself; the visual

information. There is nothing more to it than what you see, there’s no trick – no slightly

better experience requiring your physical experience. That is what information painting is.

10

Passion art

Many of the things I think are important in painting: clarity and decisiveness of the line, the

skill to compose a picture through simplification of space and figuration and what perhaps

could be called a disciplined use of color, all took cover during the reign of modernity. They

sought shelter in what was later to be referred to as popular culture, where they could

evolve and shape a new, characteristic language. They were widely spread through the

distribution of comics and more people than ever could look at line drawings and learn some

basics by copying their favorite comic book artists.

I have no specific feeling towards pop-art, it just so happens that many of the things I care

for and think are important and beautiful are categorized as pop, since they belong to a

certain culture, but should perhaps be called pass-art – for passionate – instead.

2-D alliance

I see little need for a distinction between painting and drawing today – they are birds of a

feather and should stay together. Contrary to how painthings distinguish themselves from

paintings by demanding real space and the physical attendance of the viewer to fully

experience the materiality of the work, drawing shares the same principles of visual

communication on a strictly two-dimensional plane as painting and its ideal form should be

the same: visual information only. They have only been separated because of two tiny – and

to my mind, completely unnecessary – reasons. First, drawing is generally considered to be

preoccupied with the line – preferably in a black and white setting or any other

monochrome scale. Second, there is a slight material difference, dictating drawing is this

medium and painting is that. But to go back to the cave paintings; they are as much drawings

as they are paintings. Does drawing become painting simply because it is filled in, and does

that then make painting with lines drawing? No, that is simply too fuzzy; I think they are

wrongfully separated. It is perhaps best to put it like this: the historical separation is

understandable, because you had only material, and subsequently expressional differences

11

to go on, but it is no longer necessarily so. Roy Lichtenstein, to use an exemplary, historical

blurring of the distinction, already made it quite clear in the 60’s with his paintings of comic

book drawings, that the separation is no longer necessary.

Conflict of the surface

The Conflict of the surface is a term I originally invented for dealing with the internal,

structural questions of painting –the varying compositional, stylistic, and technical ways to

create the illusion of space on the picture plane. When two or more different styles – or

elements – meet in the same picture, they each struggle to gain the viewer’s interest in a

competition for focus of attention. Looking at, for instance, a mix of the clashing

characteristics of a very distinct logo next to or on top of a realistically painted part, you

alternate between different ways of reading the painting as we have different ways of taking

in different types of information.

In its extension, the term came to include questions related to showing painting, i.e. hanging

situations, and ultimately questions related to the significance of the surface itself – which

gave birth to the term painthings.

Confusion of origin, mixing of styles

Today, our relation to time and place is completely flattened by the images on the internet.

In a very interesting way, I might add. It is a confusion of origin; no history, no cultural

connection, just a flurry of styles and aesthetics to pick and choose from. This is what I

meant when I said earlier that painting has far from exhausted its potential; lots of things

that have been overlooked, or to be fair, haven’t been possible (which is only natural, given

12

the fact that communication of images was much more limited and the availability of

information about old or foreign paintings was very restricted) are possible today. Endless

stylistic combinations and compositions are readily available to us for our immediate

enjoyment and inspiration: a global, up-to-date bank of ideas.

With the internet, any form of imagined chronological timeline has been dissolved and what

exists in its place is what I like to think of as a panoramic view of styles and expressions, with

a complete disregard for – or rather inability to share and produce – any cultural,

geographical or other on-site specific contextual information. Which, to my mind, is never

present in any mystical lingering way in any form of painting anyway, but can only rely on

the way any such cultural flavors or specific traits might have been made visible in the

painting, stylistically and content wise; the surroundings are always only second in the

reading of a painting. Suggesting otherwise immediately moves you over to the field of

showing painting in real space, which is obviously something quite different.

It is a cultural equalizer: on a particle (which is to say pixel) level, there is no telling what is

fine or foul culture; there’s no high-brow, no low-brow – there’s only no-brow! I have made

a piece constituted of two monochrome pixel-realistic paintings, each 1x1 pixel in size, to

demonstrate this. One is a faithful recreation of one of the brightest pixels in the digital

documentation of Gerhard Richter’s Betty, from 1988, which I downloaded from his

homepage. It is called Bright Betty. The other is an equally faithfully recreated pixel from a

screenshot from the Nintendo game Super Mario Bros.3, which was also released in 1988.

The specific pixel I chose to paint is the button in Mario’s pants. This painting is called Mario

Button.

Showing

In a gallery setting, I like to think of showing painting as something similar to comics, a form

of narrative constructed of consecutive images along with text (although the text part is not

necessarily required). It doesn’t have to be a continuous narrative, from a to b, as you would

13

normally expect from a comic, but still all related to each other – sort of an exploded comic;

a puzzle to be laid out in the mind of the beholder in order for it to make sense. On this

level, the paintings are both themselves – with their own compositional and stylistic

concerns, each communicating their own visual information – and part of a group, acquiring

a second level of meaning in their relation to other paintings. Showing them next to each

other or far apart, you can either emphasize the struggle for attention they will inevitably

get into, or try to avoid it. This is only natural; you show two things at once, you have to

choose in what order to look at them. It is also where a painting’s social skills come into play:

a very undemanding painting might be easy to combine in a gallery space, whereas one with

a bold and challenging composition might not. It has to do with the conflict of the surface in

its extended sense: the room. This level is no longer painting, but showing; construction of

meaning by arranging the relation between two or more paintings in the gallery space.

Video games

Video games brought a new way of seeing into the field of painting, or perhaps a re-new way

is a better description. They have given us a speed-lecture in simplification and creation of

illusion of space (well, it has been some 60 years now, but still, compared to the history of

painting and the evolution of seeing and realization, I’d say the evolution of videogames

have gone by fairly quickly).

Granted, the history of painting has been available to the creators of video-games – they too

have learned from the old masters – but they had to reinvent painting through forced

simplification and a very limited palette due to what was technologically possible, so even

when they knew how to do it classically, they had to come up with a much more scaled

down way of doing it. Super Mario for instance was given many of his distinctive features out

of simplification reasons.

14

You could say video-games went through the reversal of the quest for the final painting:

starting with the most scaled down abstraction and moving towards realism. With

technological (hardware) advancement there was sure to follow an aesthetic progression. It

went through a beautiful pointillistic phase – although at this point I would rather call it

pixellistic – during which the level of detail increased, shadows on clothes and bodies

became technically possible to paint, and now it’s on the level of photorealism, having in

many cases abandoned the painting of earlier games, but it keeps evolving as a thing on its

own.

Digital painting

Throughout the history of painting – if you care for a moment to see it as I do – what until

now has only been the impossible dream of painting as non-object is suddenly possible.

Technology has reached a level where it allows us to get as close to the original vision as

possible. And it keeps evolving, at a steady, unbelievably high pace. Painting can finally be

what it has always wanted to be – a man-made production of an image. That is why I said

earlier on that it can finally begin.

David Hockney, to use a famous example of someone who has been working with digital

painting, has in my opinion missed the point with it. He uses it as a tool just as any other;

only this is conveniently smudge-free. It is not the novelty of digital painting as a trendy, fun

and high tech means, but its possibility of being an end – a way of painting as close to the

original idea or observation as possible. Painting that no longer has to be concerned with

producing an unnecessary object, which – due to specific physical features signifying its

uniqueness – will always be greater than its documentation, but rather a tech-metaphysical

existence of a painting. A painting that exists only as information; thus it is both itself and its

own documentation at the same time. This is what I call information painting

15

(K)not related

If you paint because you want to be able to share your ideas with someone else through a

visual message, and that in itself is self-sufficient, non-dependent on an exclusive physicality,

you shouldn’t have reason to oppose what I’m saying. Most painters I know, naturally, as a

form of instantly initiated subconscious self defense mechanism, oppose it simply because it

threatens everything they think they are involved with. Painting is to this day helplessly

intertwined with its physicality. Perhaps one could make the following allegory: Painting was

once forcefully wed to Physicality; only this happened so long ago that history has blurred

the fact that the marital knot was initially tied by force and not love. But the world soon

forgot about the original lovelessness and they were considered an ordinary couple, much

like any other. Today, they are still widely and firmly believed to be happily married, which is

why any attempt to untie the knot is generally frowned upon.

Even with the digitalization of the medium, or perhaps better: the discipline, the basics for

making paintings will never die; if you work figuratively, it is still advisable to study a bit of

anatomy; developing a feeling for color is not something that suddenly doesn’t apply, just

because it goes digital; and you probably want to take a look at composition as well. Or you

could simply choose to refuse it all – that choice is just as hopelessly boring in digital painting

as it is in physical painting. It is still and always will be dependent on the hand of the artist,

the mouse – which if you’d prefer could be regarded as an oddly shaped brush – won’t

accomplish much without the hand to control it. The only change is that the physicality is

gone. Everything else – the stuff that really matter – is there.

$

Perhaps the best known example – which is pretty dull in most aspects, but still worthy, as it

were, of a thought – would be money. Money has since long gone through the

metamorphosis from object to information, and has not lost its value because of it, and

people in general seem to have very little problem with that.

16

Gallery owners and collectors who, for entirely separate reasons than painters, might

shudder at the very thought of painting as non-object can be somewhat reassured that

commerce may proceed still. The objects might fade, but trading value never will. They can

still go on, and we painters too, dealing in information instead of objects. Without the

painter: no painting – whether physical or not. To me, one way to get around losing all hopes

for making a living as an artist in times of fading significance of objects would be to make

certificates validating the authenticity of the information paintings, similar to how Sol Lewitt

seems to have gotten around unauthorized production of his instruction pieces.

Human

Finally, I would like to say that a painting has very little to do with its traces, its drips and

scratches and splashes and what have you. It seems to me a strange fixation with an idea

that we should somehow have to prove our involvement in the process of making a painting

by leaving traces of physical presence. Those are to me desperate attempts at clinging to

some form of proof of human error, which I don’t think needs to be displayed – at all – as

though the humanity of it somehow should prove that it is painting. The real human aspect

of painting is that we – humans – have the capacity and privilege to select and produce

images we think are meaningful and want others to see. That is strong evidence of a very

personal and unmistakably human connection. If a computer were to paint an image for me,

and say “this is what I think is beautiful and special, you should see this” – I might give up.

But I don’t think that is liable to ever happen. Cars may outrun us, computers outthink us,

but no thing can outfeel us; passionately we do what we do.

.jpg)

2.jpg)