Luke Dowd

ROD BARTON, LONDON, UK

In his book Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before(2008), Michael Fried draws attention to the use of workplaces in Jeff Wall’s photography: corners of garages and storerooms whose patinas of grease, worn tools and scuffed surfaces imply intricate histories of toil. Indeed Fried goes further and suggests that such spaces signify belonging in a particularly rich and compelling fashion, with whole worlds being implicated in their distressed textures.

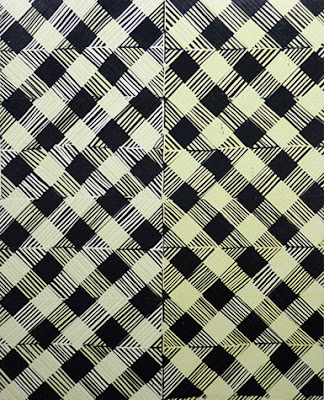

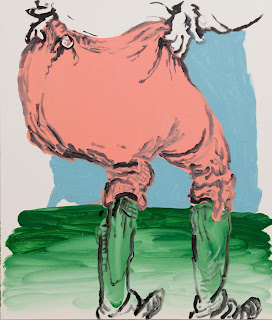

Luke Dowd’s approach in his recent work couldn’t be more different. His show at Rod Barton included eight pieces, several of which drew on his own workspace. For example the four paintings which occupied one corner of the small space – Blue 1,Blue 2, Green and Gold (all works 2011) are apparently derived in some way from a tabletop in Dowd’s studio. Yet instead of supplying the evidence of an authentic, organic life-world that Fried sees in Wall, these images have a spectral, evanescent quality, somewhere between an X-ray and a brass-rubbing. The striations, blots, shadows and spillages of which they are composed merge, smear and deliquesce, defying location even as they appear to stem from it. Likewise their internal spaces are folded in dimensions so convoluted and mobile that the eye seems to move through pulverized, molecular vistas rather than anything scaled to the human world.

By contrast, Unfolded Moon supplies a more stable image. The familiar sphere is split into eight sections, as if a paper napkin has been carefully opened out and smoothed down, retaining its creases. As with the aforementioned pictures, figure and ground mesh and merge, the pocked and pitted surface of the satellite bleeding into the bleachings and fadings of the picture plane. However the central image is intact and serenely dominant, and the fact that this moon has been ‘unfolded’ and made available to us suggests an art that still has ambitions to represent the totality.

This was an exception, however, and the tone of the show remained one of displacement and undecidability, considering the precarious nature of artistic production itself. The most telling piece in this respect was a large canvas in lurid red, depicting a studio window. We can see the wrinkled traces of a sheet blocking out the light which nevertheless comes through, starkly outlining the grid of nine panes. As such, Red Window is a powerful and instantly recognizable image. What’s more, given that the piece is life-sized, the viewer experiences a strong sense of a situated spatial relationship. Standing before it one cannot but feel the incipient torsions of the everyday act of looking through such an aperture. It is all the more disorientating then that we cannot grasp the relation in the conventional way: are we outside looking in, or vice versa? Is the light that throws the frame into relief natural or artificial? One lesson of this image, and many of the others in this thought-provoking show, might be that the very idea of a bounded, stable workplace, guarantor of a consistent self or world, is now an untenable one.

Conor Carville

.jpeg)

.jpeg)